One of the greatest stressors parents of gifted and twice-exceptional children face involves battles with the school. Yes, battles. Of course, working with the school shouldn't be adversarial. But sometimes it can seem like an uphill slog as you attempt to enlist the school's support.

Advocacy can be a daunting task. It is an unexpected additional burden that parents of the gifted must endure. No parent wants to aggravate the teacher entrusted with their child's education. No parent wants to be seen as pushy or elitist or demanding. No parent wants their efforts to backfire; teachers are human and might feel angry or hurt, or even take out their frustrations on your child if they suspect that their competence or motives are under attack.

(*For resources related to parenting support, see this link about an upcoming workshop listed below.*)

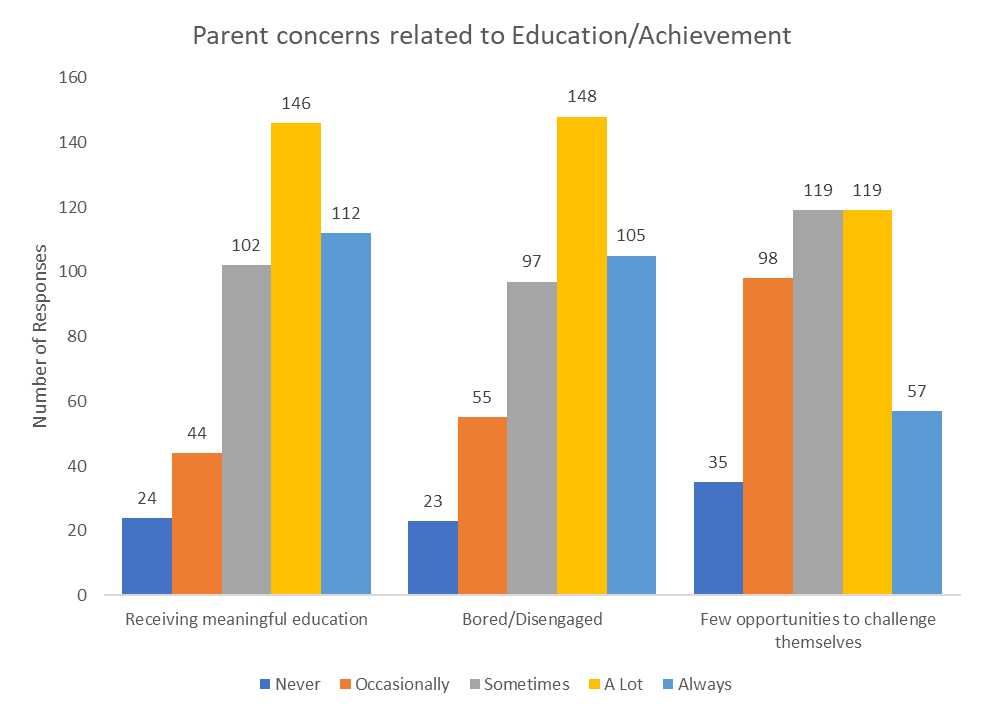

Findings from an online survey I launched in 2022 - with results shared in my recent book - confirmed that parents clearly struggle with concerns about their child's school. For example, 60.2% worried "a lot" or "always" about whether their child would receive a meaningful education, whether they were bored or disengaged (59.1%), and whether they would have opportunities to challenge themselves (40.1%).

These findings are consistent with previous research. For example, Renati and colleagues noted that 50% of parents surveyed complained about a lack of school support, and Alsop reported that less than 20% of parents viewed their child's teacher as helpful. Rimmlinger also found that one of the greatest identified stressors among parents stemmed from a lack of gifted support available within their child's school.

How can you form a collaborative working relationship with your gifted child's teacher?

1. Assume that the teacher is your ally.

Let's face it; teachers don't enter the profession for financial gain! Most embark on their teaching career with enthusiasm and a selfless desire to work with children. Even when they feel burned out, they rise to the occasion and show up each day to teach our kids. Remind yourself of their dedication and positive intentions as you advocate for your gifted or twice-exceptional child's needs. Present yourself as an ally in their efforts; let them know that you appreciate their commitment and hard work understand the limitations consistent with education within a large classroom. When your child's teacher misses the mark, remind yourself that it is not intentional, but perhaps, due to the stressful demands of the classroom or limited training in gifted education and giftedness.

2. Avoid using the "boredom" term.

Teachers want their students to feel engaged. In reality, though, meeting the demands of students with diverse cognitive abilities is a monumental challenge. As long as schools adhere to a policy of "differentiated instruction" and a refusal to consider ability grouping, teachers face impossible choices each day. Do they address the unique needs of struggling students, frustrated gifted students, or the majority of neurotypical students within the classroom? As parents, we know that our gifted children often feel bored, since most teachers cannot easily pivot from their lesson plan to address the faster pace and depth of learning these students crave. But no teacher wants to hear that a student is bored. Instead, share specific complaints, such as how much your child's mind wanders, that they become distracted during specific topics or assignments, or that they rush through homework with little effort.

3. Share what works at home.

Let your child's teacher know what strategies work best at home. This provides guidance for what also might help within the classroom. Does redirection work? Do creative strategies (e.g., drawing what they feel) provide a beneficial outlet? Does your child need a quick energy break when frustrated? Sometimes, children "hold it together" and display ideal behavior in school, but "meltdown" within the safety of home. Their distress at school may be less apparent; nevertheless, they may show signs of disengagement, such as constant doodling, heads on their desks, or staring out the window. Share the signs you notice at home that precede a full-blown behavioral eruption and the intervention you find works best.

4. Address behavioral and emotional concerns

If your child is displaying disruptive behaviors within the classroom, more intervention is needed. Behavioral problems and inattention are signs that your child is disengaged - and these behaviors take a toll on their teacher as well. Let the teacher know that you understand how difficult and frustrating this is for them and engage with them as an ally. If your child struggles with anxiety or perfectionism or twice-exceptional concerns, such as ADHD or a learning disability, help the teacher devise strategies for offering support. Sometimes, a guidance counselor or school psychologist can be enlisted to develop a plan and monitor progress, and an IEP (Individualized Education Plan) may be necessary to document the need for additional support. On another note, even if your child is not disruptive, you can mention that behavioral problems might arise if they feel disengaged. This realistic concern might motivate your child's teacher to offer more engaging and challenging assignments.

5. Offer cost-effective solutions

It's not your job to find budgetary solutions. I know, I know. Many parents of gifted children are weary and resentful about the amount of time spent advocating and figuring out solutions that ideally should come from school administrators. In the gifted parenting survey mentioned earlier, 41% of parents claimed that they felt resentment "a lot" or "always" about the necessity of advocating within the schools. Nevertheless, if you can suggest a cost-effective option, your child's needs may be met more readily. For example, subject or grade acceleration options cost nothing. Clustering highly able students together within the classroom when group projects are required is an easy choice. Let the teacher know that you understand the limits of what can be accomplished in a given day and that you are there to suggest as many easy and inexpensive options as possible.

Of course, even with the best of intentions, sometimes communications break down. If you reach an impasse, it may be time to speak with the gifted supervisor, the director of special education, a guidance counselor, the principal, or administrators and school board members. But working with your child's teacher first is ideal - and less time intensive for you. And don't forget to enlist support from family, friends, and others who advocate for the gifted as you venture forth in your advocacy efforts.

Here are a few related articles:

Gifted education: Why is it so controversial?

Three essential tips for teachers of gifted children

25 signs your gifted child is misunderstood at school

Six tips for communicating with your gifted child's teacher

No comments:

Post a Comment